Fluorescent penetrant inspection (FPI) is a popular inspection method that offers a range of sensitivities for different types of products and flaws. It’s fast and suits various materials and components. Plus, it doesn’t harm the inspected part in any way. FPI is a relatively simple process that can be used with almost any non-porous material. Let’s take a closer look at what fluorescent penetrant inspection has to offer.

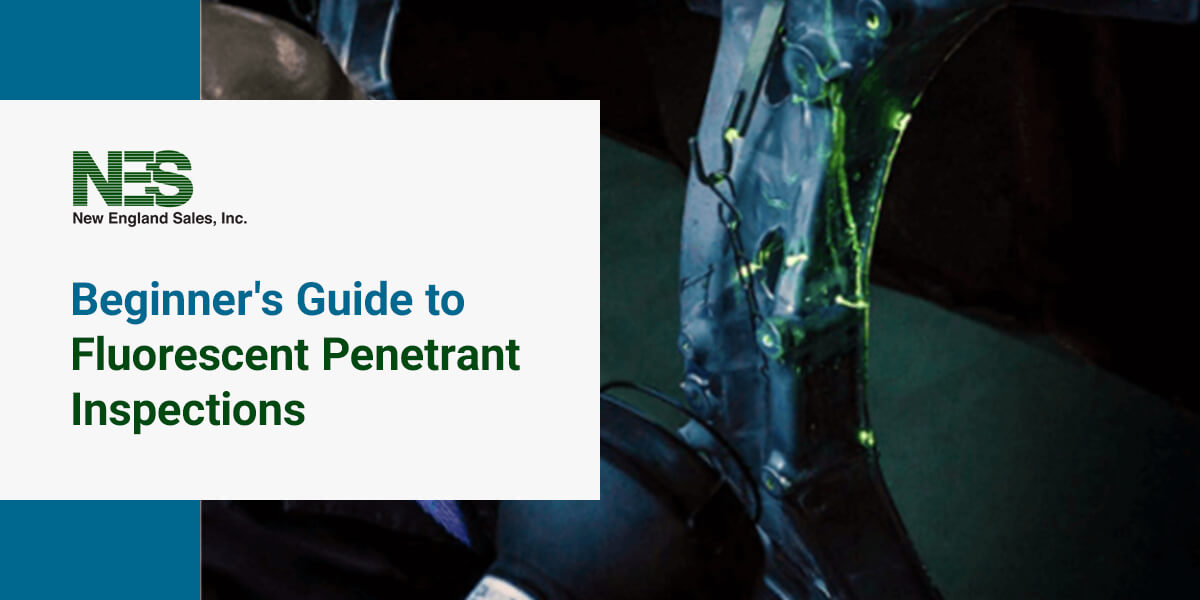

Fluorescent penetrant inspection is a method of non-destructive testing (NDT), which leaves the inspected material intact. In FPI, a fluorescent dye, also called a penetrant, is applied to the material’s surface. The excess penetrant is removed and a developer is applied. When placed under ultraviolet light, surface defects, such as cracks, fractures and seams, become “highlighted” and can be addressed accordingly. As the name implies, these flaw indicators appear fluorescent, helping them stand out against their background color.

Since it is non-destructive, you can use FPI on parts that will be placed in service or are already in service. It is suitable for non-porous components made of ceramics, plastics and metals.

FPI offers several benefits. It is:

The importance of liquid penetrant testing and FPI are clear across industries like aerospace, automotive production and power generation. The benefits of FPI for the aerospace industry, for example, include its ultra-high sensitivity, which is necessary for inspecting critical components.

Low-sensitivity FPI works well for many businesses, too, and can be a better choice for some types of flaws and components, like those with rough surfaces.

There are three key parts of any FPI process that will determine its effectiveness and suitability for a specific component. These elements include your choice of penetrant, removal method and developer. They work together to reveal the flaw and provide contrast without damaging the part or reducing sensitivity. Every approach is different, and you’ll need to consider factors related to your part, processes, flaw type and budget.

Penetrants primarily make flaws visible through different mechanisms. They produce a flaw indicator — the highlight or discoloration — that is much larger than the flaw itself and has a high level of contrast. These are two features that help the human eye better see the flaw.

Typically, you’ll choose between visible dye penetrant and fluorescent penetrant. Visible dye penetrant is usually bright red and paired with a white developer, which serves as the background. With fluorescent penetrant, the flaws emit a bright glow in a wavelength to which the human eye is particularly sensitive.

Typically, fluorescent dye offers the best sensitivity. It just requires a dim environment and an ultraviolet light. Penetrants come in a range of sensitivity levels you can select based on the application.

After applying penetrant, the excess material needs to be removed. The method of removal affects how well the penetrant works and what kind of equipment is needed to complete the process. Both fluorescent and visible dye penetrants can be removed with the following methods:

Soluble removal penetrants are quick and offer the highest sensitivity, but they aren’t very practical for high quantities or large parts. If overwashing is a concern, one of the post-emulsifiable options is likely the better choice. They require an extra step but can improve sensitivity.

Developer brings penetrant out from within the defects and spreads it out across the part’s surface so it is more easily visible. It helps the penetrant fluoresce, or emit more light. Some developers also increase contrast by creating a plain white background behind the flaw.

Developers primarily differ in how they’re applied. Depending on your part and process, you can choose from spraying, dipping or brushing, thanks to several different forms:

Your process and parts will determine which developer makes the most sense for the speed, costs and quality demands of your operation.

FPI is a relatively quick process that requires cleaning the part, applying and removing the penetrant and developer and finally inspecting the part.

First, the part’s surface needs to be completely clear of any contaminants that would interfere with the inspection, including paint, dirt, grease, varnish or metal smears. Materials like varnish and grease have some elasticity to them, so they can stretch over a fracture, keeping the penetrant from entering it and revealing the flaw. Debris can also make the excess penetrant more difficult to remove and make the inspection process more challenging.

A strong cleaning process is essential to remove these contaminants. It’s important to make sure the cleaning process doesn’t leave any residue of its own that would interfere with the FPI process.

You can apply the penetrant in several ways, depending on your chosen penetrant and developer. Consider your operation carefully to determine which will work best for your parts, equipment and process.

Once applied, the penetrant needs time to dwell or actually enter the defects. You can choose from immersion dwelling and drain dwelling.

In immersion dwelling, you leave the part submerged in the penetrant. To drain-dwell, the part is pulled out of the penetrant and drained. Drain-dwelling typically offers higher sensitivity because evaporation leads the penetrant’s dye to become more concentrated.

Dwell time can vary depending on a wide range of factors, including:

Typically, the penetrant manufacturer will recommend a dwell time, but some trial and error are often necessary, too. Still, some applications or materials require specific dwell times according to industry standards, such as military specifications or ASTM International standards. When in doubt, longer penetrant times are usually best, as long as the penetrant doesn’t dry.

The process of removing the excess penetrant will vary widely according to your penetrant, developer and methods. Whatever strategy you use, it’s crucial to avoid overwashing, removing penetrant when wiping or otherwise affecting the amount of penetrant in the flaw. If necessary, dry the part.

Again, applying developer can look vastly different depending on your materials and process. Apply the developer as needed, usually in a thin, even layer that’s as uniform as possible. If you use too much developer, you may cover up flaw indications, but too little developer may not develop the indicator enough. Let the developer sit according to your application and dry it again if needed.

Once the flaws appear, you can inspect the part. Place it under ultraviolet lighting in a dim room and assess it for flaw indicators. Lines or dotted lines can indicate cracks, laps and cold shuts. Most indications will grow and spread, particularly if wide and deep, but even minor dots or areas of color can grow. After inspection, clean the part to remove any materials left over and process it accordingly.

Different applications call for different levels of sensitivity. Higher sensitivity levels will show smaller defects, but they also come with more background fluorescence, which reduces the contrast between the part and the background and can make defects hard to identify. According to AMS 2644, fluorescent liquid penetrants fall under one of five categories:

The sensitivity level you’ll need is typically determined by industry specifications, especially if safety-critical parts are involved. In the absence of an established sensitivity level, you may need to do some experimentation to find the right one. Rough surfaces tend to do better with low-sensitivity penetrants, while smooth, highly machined parts may are often better served by high-sensitivity penetrants. You might also need to experiment to determine proper timing, like dwell and rinse times.

Although small-scale FPI can be accomplished manually, it is typically slow and not as reliable. It also won’t scale up for consistent operations, like manufacturing lines. Instead, you can streamline and improve the process with FPI equipment. FPI equipment can handle everything from penetrant application to inspection, all in one piece of machinery. For large-scale production, automation is a must-have.

Regardless of the size of your operation, you’ll see the importance of FPI through speed and accuracy. Automation is a great way to both speed up large-scale work and minimizes the chance of errors by leaving it up to machinery. It can reduce labor costs and help you identify flaws according to a more consistent, reliable system.

FPI equipment plays a vital role in part preparation and inspection. They use affordable, fast mechanisms to help improve the consistency and quality of every part that goes through your facility.

At New England Sales, we’ve partnered with industry leaders like Ramco and Proceco to provide a wide selection of high-quality FPI equipment for businesses of all types. If you’re looking for a cost-effective, fast inspection method, we can help. With decades of experience in even the strictest of industries, we’ll help you every step of the way with on-site visits to determine the best fit for your organization. We provide turnkey installation, ongoing service and repairs throughout New York and surrounding areas.

Reach out to our experienced team today to get started with FPI systems.